From Aya Nakamura in France to Selena Gomez in the U.S., pop stars are collaborating more and more with Nigerian artists like Rema or Burna Boy. Les Echos looks into how Afrobeats went global — and where it’s going.

LAGOS — The sound is surprising, with a fast tempo, typical of Afrobeats, that is accompanied by violins. Nigerian music producer and songwriter Andre Vibez is putting the finishing touches on a new track in one of Mavin Records’ recording studios in Lagos.

Just last February, Universal Music Group bought a majority stake in this record label, which is responsible for making Nigerian Afrobeats a global phenomenon. Universal’s leaders may not feel very lost when they come to Nigeria’s economic capital to conclude the deal: the two grey buildings topped with a roof terrace and the white Jeeps at the entrance seem to have been teleported from Los Angeles.

The difference is that the premises are surrounded by barbed wire and monitored by security guards. Lekki, this district which was still a swamp 15 years ago, aspires to become like Dubai. But a makeshift camp on the empty lot along the Atlantic Ocean shows the reality of this chaotic megalopolis of more than 22 million inhabitants.

In a country where 40% of the population lives with less than $2 per day, Vibez knows he’s lucky.

“I own four houses in Lagos and am looking at buying an apartment in London. I have three cars. I’m going to open my restaurant soon, I’m thinking of launching a brand of bottled water, and I’m working on a clothing line,” says the 30-year-old whose Versace socks stick out of his sneakers.

“Calm Down”

The son of late Nigerian singer Victor Uwaifo, who earned the continent’s first gold record in 1965, Vibez’s life changed radically two years ago when he composed “Calm Down” for the young Nigerian singer Rema.

With its catchy chorus, the song quickly became the biggest hit in the history of African music. The use of Pidgin — a mix of English and Yoruba, Hausa, or Igbo, the dialects of the three main ethnic groups of the former British colony — wasn’t an obstacle to international success. On the contrary, this vivid Creole has a very musical quality.

“The English language is used in the art of hiding emotions, and Pidgin in the art of expressing them,” Panji Anoff, manager of Ghanaian artists, said in the book A Quick Ting On Afrobeats by journalist Christian Adofo.

“Calm Down” was among the most streamed and sold singles in 2023, thanks in part to a remix with American singer Selena Gomez.

Global tracks

This collaboration is not an exception: more and more Western singers are seeking to work with Nigerian artists.

Aya Nakamura, the most-listened-to French-speaking artist in the world, has released a song and music video (filmed in Lagos) featuring the deliciously androgynous voice of Ayra Starr. Signed by Mavin Records, Starr has enjoyed dazzling success since the release of her single rush “Rush.” Last year, the 21-year-old artist was also featured on a song by Ninho, the French rapper who sold out two concerts at Paris’s Stades de France in a few minutes.

But France is just starting to ride a wave that has already swept through English-speaking countries. In 2016, Canadian rapper Drake invited Wizkid to sing on his hit “One Dance.” The tables were then turned, in 2021, when the artist from Lago’s working-class Surulere district asked Canadian star Justin Bieber to sing on his hit “Essence.”

English singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran has worked with singers Burna Boy and Fireboy DML, going as far as to sing in Yoruba. Even the world of country music is interested in Afrobeats sounds: composer Niphkeys was recently invited to Nashville by a producer.

On Spotify, streams of Afrobeats tracks have grown sevenfold since 2017.

On the terrace of the Hard Rock Cafe in Lagos, just before a popular Monday night dance event, DJ Obi can’t believe how far he has come: “The municipality of Boston has just announced a Burna Boy Day. When I was a DJ there, 20 years ago, I couldn’t even put African music in my set.”

The success of Naija artists is the latest sign of a massive shift in the music industry, where “the U.S. is no longer the nerve center of pop,” says Mehdi Maïzi, a hip-hop manager at Apple Music France. On the service, streams of African tracks grew four times faster than for other genres worldwide in 2023.

Same thing at Spotify: African artists may not have attained the success of Latinos, who represented four of the platform’s Top 10 of most-listened-to artists in 2023, but streams of Afrobeats tracks have grown sevenfold since 2017.

Megachurch choirs

While some artists, such as Wizkid, say they do not belong to the “Megachurch” category, this catchall word applies to songs with a fast, driving tempo, mixing African percussion and local genres such as jùjú, dancehall, hip-hop, reggae, and R&B.

This style is not exclusive to Nigerians, but the residents of the most populous country in Africa — which is expected to become the world’s third largest in 2050, behind China and India — are its champions. Of the five names nominated in the new Best African Music Performance category at this year’s Grammy Awards, four were Nigerian — although it was South Africa’s Tyla who took home the prize.

In Lagos, it’s easy to understand why that is. Evangelical megachurches have sprung up across the sprawling city, which has almost as many Christians as Muslims. A large part of Afrobeats artists develop their skills in gospel choirs, often accompanied by an orchestra.

Already famous for its film industry, Nigeria also has a long music tradition, marked in particular by Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat (without the “s”), a mix of jazz and Yoruba polyrhythms, from this dominant ethnic group from the southwest of the country. Against a background of gbedus and shekeres, dried gourds covered with beads or cowrie shells, the “Black President” denounced the colonial mentality and government corruption at the time.

Unfavorable conditions at the start

This heritage is still very much alive at the New Afrika Shrine, an open-air entertainment center in the historic and popular part of Lagos, which is separated from the upper-class islands by a bridge. On Sunday evenings, people enjoy donuts while sipping palm wine on red plastic chairs. On stage, Femi Kuti, Fela’s eldest son, makes the room dance, led by the dancers’ swaying hips.

But today’s Afrobeats no longer has much in common with the music of the pioneering artist. Kuti’s death in 1997 coincided with a surge of songs from Michael Jackson, Tupac, and Notorious B.I.G., triggered by the opening of radio and TV frequencies to private companies.

Among them, Cool FM, which was founded in 1998: “At the time, we played mainly foreign music, especially from the U.S. There were few Nigerian artists, and it was difficult to have sounds with a quality equivalent to that of the Western world,” says the radio’s boss, Lebanon-born Serge Noujaim.

To finance your career as an artist, you needed either a rich family — like Davido, who doesn’t hide his status as “Omo Baba Olowo” (“Son of a Rich Man”) — or to turn to the underworld. “Funding came from drug dealers, crooks… Artists sang their praises, like Leonardo da Vinci with the Medici,” says Joey Akan, author of the Afrobeats Intelligence newsletter. The song “Yahooze” by Olu Maintain was inspired by internet scammers the Yahoo Boys.

A new sense of pride

But the dynamic is changing with the growth of the Nigerian diaspora in Anglo-Saxon countries.

“This immigration started with the structural adjustments of the 1980s, which led to the collapse of educational institutions and to currency devaluation,” explains Jaana Serres, author of a thesis on Afrobeats at Oxford. After spending the month of December in the country, these often highly educated emigrants would leave Nigeria with a suitcase full of CDs. Then they played this music at major universities and entertainment companies like MTV, where they held executive positions.

In the UK, the movement came with — or triggered — a new sense of pride among African immigrants about their origins. “For a long time, we were made to feel ashamed of our parents’ strong accents and our culture, leading us to deny our African heritage and pretend we were from the Caribbean,” writes A Quick Ting On: Afrobeats author Adofo, who is of Ghanaian origin.

Viral dances on TikTok

The real turning point came with the Internet revolution. “It put us on an equal footing with the rest of the world,” says Abuchi Peter Ugwu, CEO of the record label Chocolate City, in his office decorated with posters of James Bond and the Beatles. Between two calls to restart the generator — a daily habit in this city where the National Electric Power Authority (NEPA) is nicknamed “Never Expect Power Always” — the label’s boss gave a tour of the studio where Nigerian singer CKay recorded his hit “Love Nwantiti.”

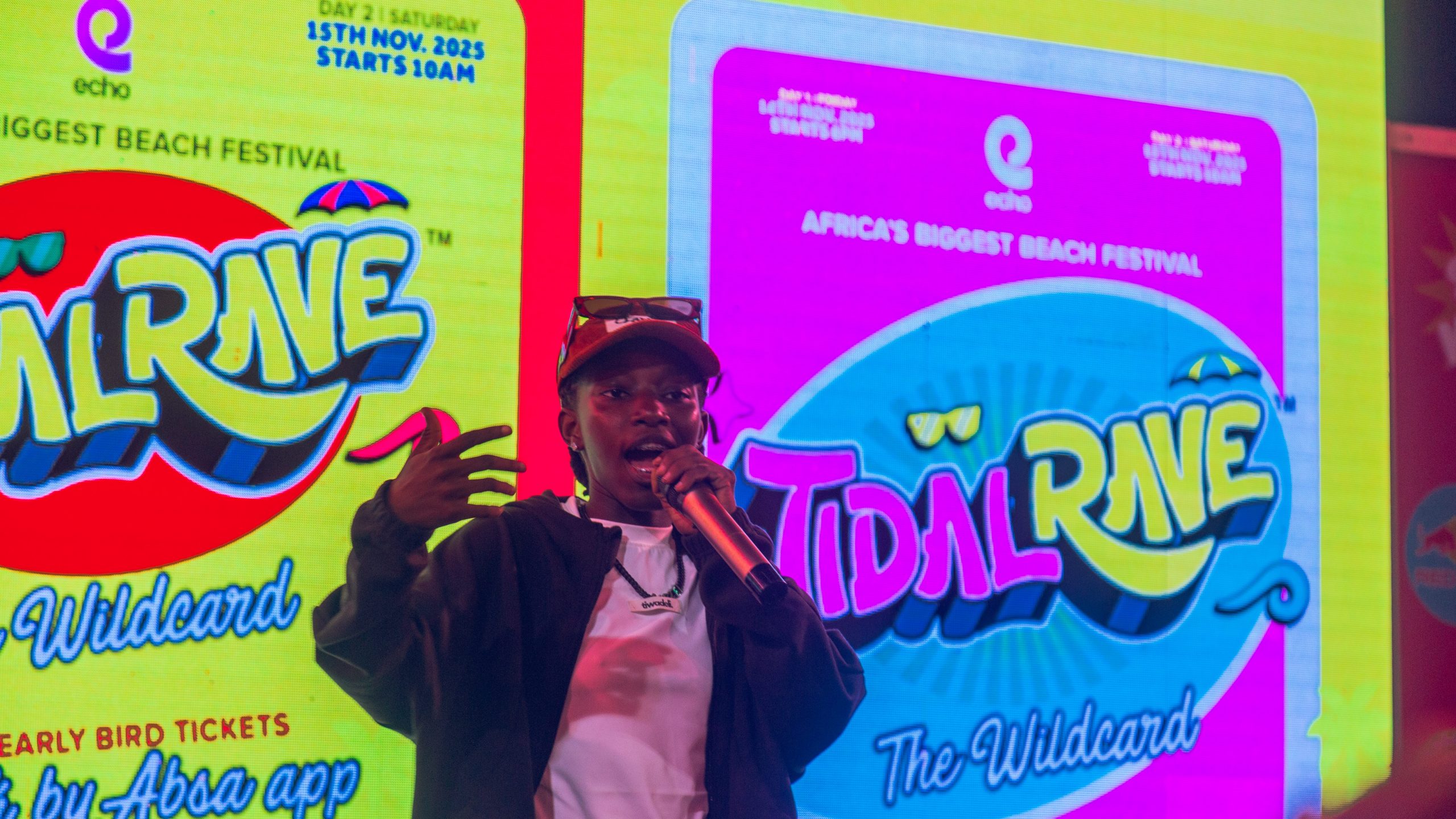

Two years after its release in 2019, the song enjoyed a second life on TikTok. Nigerians have become masters of going viral on social media thanks to dance moves that are imitated around the world.

These skills are now sought after abroad: Cameroonian artist Kocee is visiting Nigerian choreographer Kaffy. In her living room, the dancer improvises choreography for his new song “Credit Alert,” miming the absence of notes in her bank account. “You’re going to get millions of views on TikTok,” she says.

Making a living

What also pushes Nigerians to export their music is the fact that they can’t make a living in their home country. For a long time, music was mainly listened to via CDs bought in markets, all pirated — with artists paying fraudsters to distribute them en masse.

With smartphones, streaming has grown and foreign companies have seized the opportunity: in 2015, Transsion, a Chinese smartphone manufacturer with a 50% market share in Africa, launched Boomplay, before facing competition from U.S. Audiomack two years later.

The giants Spotify and Apple Music have arrived more recently, as the economic model isn’t obvious. “People aren’t eating, so how can you expect them to pay to subscribe to a streaming service?,” Boomplay manager Dele Kadiri asks bluntly. With monthly subscriptions costing around 50 euro cents ($0.54), the fees distributed to artists remain low in any case.

The same goes for concerts. “5,000 naira [$4] is the maximum price for a ticket. 50,000, that’s if Jesus comes to the concert,” Chocolate City CEO Ugwu says with irony. And even if then, Lagos lacks large events venues equivalent to London’s O2 Arena or Paris’s Accor Arena, which Burna Boy or Davido have filled easily. The city’s National Stadium is not suitable and the National Theatre has been under renovation for years.

“Foreign labels are poaching our artists and employees with salaries up to eight times higher.”

There’s one final issue: copyright. For several decades, Coson and MCSN, two music rights management organizations equivalent to BMI in the U.S., “have found themselves engaged in an unsolvable legal battle in which each claims its legitimate practice,” according to a 2021 PwC report. Royalties are therefore rarely collected, and when they are, singers and composers complain that they never actually receive them.

“There have been accusations of corruption, but today it is difficult, even dangerous, to speak out against current practices,” according to the consulting firm’s report.

Until now, Nigeria’s government hadn’t supported the music industry or seen it as a tool of soft power. But that is starting to change as Abuja seeks to move away from economic dependence on fossil fuels.

“Bola Tinubu, the president who was elected in March, created a new Ministry of Entertainment and Tourism. The government seems to have moved from the idea of controlling cultural industries to that of exporting them,” says researcher Jaana Serres.

Ubiquitous luxury brands

In this difficult context, artists have no problem signing with foreign record companies, which have started to open offices in Nigeria. “These labels are poaching our artists and employees with salaries up to eight times higher, and paid in dollars. We can’t compete because of the devaluation of the naira,” says Ugwu, whose flagship artist, CKay, moved to Warner.

Artists are also signing onto corporate collaborations. On the congested Lekki-Epe Expressway, which cuts across the archipelago, a billboard with Davido promoting Martell Cognac stands just a few hundred meters from another of Tems drinking a glass of Jameson Whiskey.

From Richard Mille watches to Ferrari and Lamborghini cars, luxury brands are omnipresent in song lyrics, which promote billionaires as heroes, including the continent’s richest businessman, Aliko Dangote, in a song by Burna Boy. The Grammy-winning artist, who calls himself “African Giant”, boasts a pan-African pride inspired by Fela Kuti — his grandfather was Kuti’s manager. But that doesn’t mean he’s an anti-capitalist.

“In Nigeria, businesses aren’t viewed with the suspicion that is so common in the West. Branding is a word entirely devoid of irony, and people use it to refer to themselves,” Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote in The Passenger magazine.

Western consumerism

This evolution has been criticised by Seun Kuti, the Afrobeats legend’s youngest son, who has revived the socialist party that his father founded in 1978.

While smoking a joint in his house, not far from the New Afrika Shrine, the artist, outspoken about his anti-elite stance, doesn’t mince his words: “Today’s songs promote the concept of Western consumerism, of frenzied individualism. These artists are cowards: they make music to make Gucci owners feel good and make poor Africans feel inferior.”

Paul Ugor, professor at the University of Waterloo in Canada is more nuanced: “The use of of an imagery of pleasure — mainly in the form of romance, consumerism and friendship — is an act of resistance, reflecting subversive access to luxury spaces to which the postcolonial state doesn’t provide access.”

New themes

With his candy pink Balenciaga sweater and matching silk hat, Nigerian singer Oxlade notes that along with many other artists, he took part in 2020 #EndSars protests against the Special Anti-Robbery Squad accused of police brutality.

“We realised that enough was enough. That we couldn’t be afraid of the police and thieves at the same time,” says Oxlade, who has signed with Epic Records France (Sony). For his first album, set to be released this month, however, he prefers to be in the same vein as “Ku Lo Sa,” the love song that made his career take off in 2022.

In a country where traditional male and female gender roles aren’t questioned and where love is necessarily heterosexual, romantic relationships remain the main theme for artists. “70% of Afrobeats songs glorify women, make them feel good,” says Nigerian singer Victony, whose song “Soweto” was Spotify’s second most streamed Afrobeats song in 2023. “But that will change. Artists are starting to feel more comfortable talking about their difficulties, mainly personal ones, but also those of growing up in an environment where electricity is a luxury.”

A sign, perhaps, that Afrobeats is starting to embrace the struggles of the younger generation.